This Fishing Life: Part I

THIS FISHING LIFE.

1969 – 1980

Part I

I’ve been prompted to put something on paper (so to speak) of my experiences during the fishing stage of my life, by my inability to remember correctly the details of the joke about ‘hauling a mine’. But that will now come in due course. So how did I end up being a fisherman?

On leaving our island farm I/we tried to find a farm or small-holding on the mainland to move to. But we had very little capital, and anything that we could afford seemed to offer very little prospect. But brother Mick, who had been lobster fishing with me on Bardsey suggested we go into the trawling business from Plymouth. He too was restless in his job as a boatbuilder with Mashford’s of Cremyll. So somehow or other he’d teamed up with a Skipper from a trawling company in Plymouth. Doug Neilson had recently lost his job (and the boat under him!) so was looking into going solo. So we formed DAM Trawlers. (Douglas, Anthony, Michael. Although Mick had wanted to be first, but Doug and I put our foot down.) As soon as they had my agreement they bought a second-hand trawler from Bob Kimble in Brixham. Dad put up the money (£7,400) to purchase the Karen Marie.

| |||||

| Douglas, Anthony, Michael. |

|

| The Karen Marie. |

She was an ex-French crabber. Fifty foot, wooden, transom-sterned with a forward wheelhouse, and after gantry. She was fitted with a 138HP Volvo Marine engine, seawater-cooled. The steel wheelhouse had a door aft, straight to the winch control. Inside, to port a short upholstered bench seat, and forward of this the hatch below. Wheel and controls and Decca screen across the front, and down the starboard side a small sink and drainer and a gas cooker. Below the wheelhouse the cabin with four bunks, with a door aft into the engine room. Aft of this, but accessible from a steel-covered raised deck hatch was the fish-room, with an opening aft to the ice hold, which had flush deck-hatches in the after fish pound. The 2-drum winch (with whipping-drums) was belt-driven from the engine flywheel. She was a comfortable little boat and served us very well for about five years before we sold her to a father and son from Bridlington in Yorkshire. ( They defaulted on the payment and Mick Walker and I travelled up to Yorkshire and clandestinely re-possessed her and sailed her back to Plymouth. The gribble in the stern-post gradually got the better of her and we scrapped her some time later.)

| ||

| Mike Walker and me. I think Mike must have been the first "hand" we ever took on. And he stayed with us right to the end. | |

|

| Doug and Mick. Look at all the Queen scallops, in those days regarded as rubbish by-catch. |

The original plans were that we would make 36-hour trips. So I envisaged leaving home early (6am.) on Monday morning, returning home on Tuesday evening.. Going back early Wednesday morning, returning Thursday evening. Presumably going to sea again after landing our catch again on Friday morning and this time returning on Saturday morning in time to land our catch for the Saturday market. Sounds alright in principle, and Mary and the kids were happy with that. But then it turned out that we didn't get back until later in the evening. So having promised the kids that I would be home on Tuesday evening, I didn't get back until after their bedtime. That was hard on them and hard on Mary too. We’d come from a life where I was around 24/7. Then to only see me fleetingly every other day, and then not until the weekend was a shock to them all. From my (our) point of view at sea, we were pushing hard to make a living. And Mick and Doug were happy with getting back later (getting one more haul in). Or we would be pushed home early by the weather, and Mary would have to tell the kids that I wouldn’t be home tonight because I came home for weather late last night and I’d already gone back to land what we had caught before going off again. So although I’d been home, they missed me entirely. Mary and I went through a rocky patch in our marriage!

|

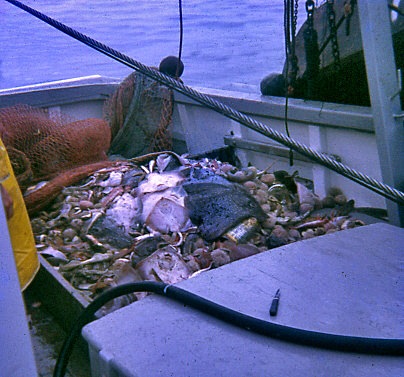

| A mixed bag of fish. Note the "rubbish"; largely Queens and Sea Urchins. |

But from a business point of view we did well. Doug was a good skipper. Most trawlers out of Plymouth at this time were using variations on the Granton trawl; a heavy foot-rope with relatively large bobbins (10” rubber tyre ‘washers’ made from sliced rubber tyres ) threaded on to a foot-rope chain. But the head-line (the top of the trawl – the trawl basically of a top and bottom netting panels joined at edge edge at the wing-ends) was several feet shorter than the foot-rope, so when it was towed the top panel was several feet in front of the bottom panel, so ‘covered’ it by several feet. So when the fish were disturbed by the oncoming foot-rope, they were already under the top panel.

But being joined together at the edges, it was a bit like towing a sack through the water; it only opened very wide at the centre, closing down completely as it neared the edges at the wing-ends. So we felt that a lot of fish would be disturbed just by the approaching headline.

But Doug had got a design for a box-trawl (don’t know where?); a much lighter trawl than the Granton, and with a rectangular mouth. So beside the top and bottom panels, it also had triangular side panels. But it had smaller 4” bobbins on the foot-rope. (The bottom panel – belly – is fastened to the fishing-line, and this in turn is linked on short 8” legs of chain to the foot-rope.) So when we made up the box trawls all three, the headline, fishing line and foot-rope had to be exactly 64ft. long. And the fishing-line and the foot-rope were joined at the wing-ends to a triangular shoe which maintained the spacing between the fishing line and the foot-rope. So when it was towed, the fishing-line and so the net was immediately above the foot-rope, with a 4” clearance of the foot-rope. This gap was important; it allowed space for a lot of rubbish (small stones, dead shell, etc) to pass without going down into the net. But also, in order to get about 12 foot of height in the mouth of the trawl, instead of towing the wing-ends on a single bridle from the doors (the otter boards) they were towed on a second bridle from the doors to the top of the wing-ends, with a substantial buoy to give the wing-ends lift. But that's all technicalities!

%20trawl%20rig.jpg) | ||

| A box trawl. Top and bottom bridles coming off the "doors", to give the high mouth opening. |

|

| The make-up of the mouth of a box trawl. |

Whatever, this box trawl seemed to excel at catching Lemon Soles. And a lot of our success in those early years came from this fish. Fishermen chat to each other, on air – long hours on watch while towing with little else to do – and inevitably how the fishing is going comes up. They are generally a bit cagey about what they divulge. But when we were talking to other skippers of our own boats – we ended up with five other boats at one stage – we were less reticent about catches. But others could listen in. So I agreed with our other skippers that we would let them know how much fish we were catching by talking about “boxes” of fish. But what others did not know was that, when we bought Karen Marie she came with a number of 10 stone (60 kg.) aluminium “trunk” boxes, and it was the number of these which I was talking about rather than the 4 stone (25 kg.) plastic boxes supplied by Sutton Harbour, our fishing port in Plymouth. So a couple of boxes of Lemons meant 20 stone, not 8. So if we were doing well on a patch of ground we could put the other boats in the Company on to it. But that fell apart when I heard another fisherman, not in DAM Trawlers, explaining to a mate over the air that I was talking “trunks”, not “boxes”!

| ||

| Our landing, sorted and graded and laid out ready for auction. |

SHARE FISHERMEN.

Before I go much further I ought to talk about Share Fishermen. There is a tradition in the fishing industry, and it is recognised by the Inland Revenue as well as the Department of Work and Pensions, that all the crew of fishing boats, including the Skipper, are employed by the boat owners (or company) as Share Fishermen. This applies to Skipper/Owners as well as fleet vessels. The crew are not paid a wage; they are paid a share of the catch! At the end of each week the value of the catch sold at auction, minus landing dues and Fishing Agent deductions, is paid to the Skipper. A fixed proportion of this (and I can’t remember now, some 50 years later, what percentage that was, or even whether it was variable across different vessels), but I seem to think it was 50% across the board) was deducted for the boat. The rest was shared among the crew (the Share Fishermen). When a hand was taken on he would be told what his share would be, and that of course depended on the number of crew, and his position in the crew.

So on smaller boats, where the owner may well have been the Skipper, the Skipper was also the Engineer, and there might be one or two deckhands. So the Skipper would get, say, 50% and the two hands 25% each. On a larger boat, and I’m thinking of the Vigilance which we ended up with, we had 6 crew, including an Engineer/Mate and a cook. So Skipper (40%), Engineer (20%) and three hands (10% each) and the cook (10%). And in those days what the crew received was cash, in a pay packet, with a note of the catch return and the sharing. (No PAYE. That was the responsibility of each member of the crew!)

An aside to being a Share Fisherman was that each man (I never heard of any women fishermen in those days) was responsible for his own NHI Stamp. But it also meant that if he didn’t go to sea on any day, regardless of cause – weather, repairs, illness, injury – he could “sign-on” at the “dole office”, and get unemployment benefit for that day. But if his ship went to sea for any reason he couldn’t sign-on. So an inequity of the system was that if the Skipper sailed with the intention of fishing, but turned back because it was too rough, the crew lost their dole. But from the owners point of view it sometimes prevented Skippers at least having a look at the weather outside the breakwater, rather than just listening to the forecast.

Next: "The Daily Grind", The Technical Bit, Stocker and more

Comments

Post a Comment