This Fishing Life: Part II

This Fishing Life.

1969-1980

Part II

“THE DAILY GRIND.”

To continue with the narrative, the day started about 6am when the catch was landed. This entailed the vessel getting a quayside berth, at least temporarily, to swing the iced boxes of fish ashore on a derrick from the fish-room. Each vessel generally had a hanger-on, an old retired fisherman living locally, who would help sort the catch. Although the catch had been iced away in boxes, all grades of each species were in the same box, but ashore, on sorting tables supplied by the market or the “agent” (in our case Mashford’s) the fish was separated from the ice and sorted into auction boxes with small, medium and large Lemons, Plaice, Megrims, etc. and each box was labelled with the vessels name. It was spread out on the market floor awaiting the auction which started at about 7.30am. Meanwhile, each vessel took on a stack of clean boxes, moved round to collect ice, discharged from a chute at the ice works, and fuel, if necessary. Somebody would be despatched with a shopping list for the trip’s groceries, and then all went into Lil’s Cafe on the Barbican for breakfast. Then away to sea.

Usually, on the way out to the fishing grounds the hands would go over the trawl, doing any repairs necessary, and generally making the gear ready to shoot, before getting out of the weather, either going into the wheelhouse (that was all there was on a smaller vessel) or below to get some sleep or lie on one's bunk reading and smoking, depending how much steaming there was to do before shooting (the trawl).

It might take anything between one and 3 hours to steam off to a favoured fishing ground. Much of our time in the early days, bottom (demersal) trawling we spent on a patch of ground at the back of (to the south of) Hatt Rocks, some 12 miles or so off Looe. And although we nearly always shot short of this and towed to the ground, it took about 2 ½ hours before we shot.

THE TECHNICAL BIT.

(You can skip this bit if it is not of interest!)

Once on the ground, the wing-ends of the trawl would be thrown overboard. Then, having checked the cod-end was securely tied/clipped, the cod-end would be payed away, quickly followed by the rest of the trawl. At this stage, all of the net would be in the water, but closely towed behind the vessel, hanging from the bridles.

(This is stern-trawling, where the gear is shot and retrieved over the stern from a gantry. Nowadays the trawl is invariably “stowed” on a net drum, so it is all wound in on the drum, rather than being hauled aboard by hand and lazy-decky – a rope for lifting the cod end aboard. But for probably a century before the stern trawler, trawls were shot and retrieved over the side of a vessel, in a slow turn, from “gallows” set forward and aft along the rail. This was often termed ‘side-winding’. Carmania was a side-winder, and so was the Vigilance when we first got her, but we quickly converted the Vigilance when we started pelagic trawling. But that’s another story. (Carmania And Vigilance were later additions to the company.) Compared with stern-trawling, side-winding is an awkward method, and with stern-trawling one can keep the weather astern when shooting or hauling if needs be, and one can be certain of shooting in the right direction to start a tow.)

At this stage one can check that all has shot clear, with no headline hitched on a foot-rope, a weight tangled, or a buoy not floating. The bridles can now be payed away on the winch. They run through kelly’s-eyes, a large open link that will allow wires and shackles to pass through, on the back-chains of the doors (otter boards). Eventually, when the bridles have been fully payed away they are checked by stop-link on their ends, which is too big to go through the kelly’s-eyes, so the weight of the gear is now taken up on the doors (which are hanging from the gantry – or gallows – by chains through the towing brackets. But the bridles are still connected to the two warps – the long cable on which the trawl will be towed - by lazy-links connected to a flat-link on the end of the warps. This flat link is now connected to a G-link attached to the door, and when this is connected the weight of the door, and all the gear is now taken by the warps. So the lazy-links are thrown over the back of the door out of the way, and the door is lifted by the warps, to release the door-chains. Now everything is hanging on the warps from the towing blocks, the big heavy rollers hanging off the gantry (gallows) through which the warps pass. They have to be big to allow flat-links and stopper-links to pass through. Now the warps can be payed away. Generally speaking the trawl is towed at about 2 ½ to 3 times the depth of water. So in 40 fathoms (80m) it would be towed at 100 to 120 fathoms (200m to 240m). The warps are marked by combinations of short lengths of rope spliced into the wire. If my memory serves me right, there was a double short mark at 15 fathoms, but I can’t remember the rest of the markings. But whatever, the winchman knew when to stop paying out wire. Then everyone settled down for, hopefully, a three hour tow. First a meal or drinks, then everyone not on watch went below , leaving the watchman to check the Decca against his charts, and chat on air to whoever might listen. No drinking! At least, not alcohol. (I don’t think I ever came across that at sea.) But a lot of smoking! An occasional look around to see who or what else may be about! But constant eyes on the track-plotter, and a radar, if there was one, and on the echo-sounder.

At the end of 3 hours or so, unless we “came fast” (got caught up on a snag on the sea-bed and stopped) before the time was up, we would be roused by the watch, and we tumbled out on to the deck, pulling on waders and oilskin smocks as we went. We were likely to be soggy with sleep; it might be dark; the sea might have risen; or it could be a flat-calm, sunny day. The drums on the winch would be dogged in; brakes off as the drive took the weight; throttle off; and hauling began. The crew were usually expected to keep an eye on the warp marks and call when the short marks came aboard, in case the winch man hadn’t seen them. Then it was a reverse of the shooting procedure. Doors hauled tight; door chains on; slack back; flat link unhooked and lazy-legs cleared; hauling bridles until wing ends in the blocks; lazy-decky unclipped from the wing-end and clipped to a heavy hauling line rigged on the stern gantry. (the gilson). The lazy-decky hangs loose down the side of the trawl while fishing, and connects to the bag-rope, which encircles the top end of the cod-end. When the decky is hauled on a whipping drum, the cod end is choked off and gradually hauled up the side of the rest of the trawl, and eventually lifted out of the water and over the transom, and it swings aboard with a crash and is caught by the bag-rope, where it rests. Now a hand ducks in under all the chafeing gear on the hanging cod-end and pulls the cod-end rope (or clip) to undo the cod end, and the catch, and all the rubbish with it falls out into the fish-pound, an area of deck surrounded by pound-boards, to contain the “catch”

As the net is hauled we are keeping an eye out for any obvious holes or damage incurred during the tow, and before the gear is shot away again some running repairs may be made. But if all is well, the cod end is tied again and lowered back over the side/stern and payed away. Lazy decky unclipped and clipped to the wing end; bridles away, and so on. Once we are fishing again we turn our attention to the catch. Basket are spread out and we sort through the heap in the pound, shovelling the rubbish over the side as we go. The catch is roughly sorted into the baskets, and then gutted into fresh baskets, washed with a deck-hose, or thrown into a fish washer, and then passed below where it is tipped into boxes (or trunks), iced, and stacked away in pounds where it can’t slide about. (In larger vessels, staying at sea for many days, the fish would be stored loose in the pounds, with layers of ice over each new addition.) Only when the decks were washed down, and the fish stowed would the crew get off deck.]

Depending on the time of day, or night, the Skipper, who may or may not have been assisting on deck, had, amongst his watch duties, either prepared a meal or drinks. But sometimes the crew just tumbled back down to their bunks. Even with full 3 hour tows, sleep deprivation soon built up. At the very least you were called every 3 hours and then on deck for anything between ½ hour and an hour. Then a drink and/or a meal and you were running into an hour or an hour and a half out of your bunk. So every three hours you might get an hour and a half’s sleep. BUT, when you came off deck it might be your watch. In this respect, the bigger the crew the better. With just three of you, every third tow you were on watch. So in 9 hours you got 3 hours kip. This was tolerable, but two-handed vessels felt the strain, so generally made shorter trips. With three of us during the winter months, when it was dark earlier, we usually tried to get the dimpsey (twilight) haul in before pulling the wing-ends aboard and heading for home. But if the dimpsey haul was later, we would head for home about 5 o’ clock. (So you see why I frequently missed the kids' bedtime.)

A section from one of our plot rolls from the back of Hatt Rocks. It shows how “well worked” this piece of ground was. At a guess it covers about 3 miles long by a mile wide. (The green and red gradations have faded; only the traces and the hitches remain.) But it doesn’t tell the whole story. This is obviously a plastic roll. When we started we used paper rolls, so this isn’t our complete history on this site. But also, we changed over to a pencil stylus because it didn’t obliterate the hitches (the red dots). But latterly we lifted the stylus off the paper, and only let it back down if we struck a hitch, or wandered off onto new ground.

Not all tows lasted the allotted 3 hours. We were working relatively clear ground, but that did not mean we didn’t occasionally ‘come fast’, when one detected a slight loading of the engine, and looking over the side the steady 2 or 3 knot passage (2 or 3 mph. or thereabouts) had ceased. If the crew below hadn’t noticed they were raised by a shout down the hatch, but the watch would have throttled back and started hauling. Usually the gear would lift off the hitch gently, and one hoped with no damage, in which case it would be shot away again. But sometimes one could feel the gear wrenching free, and the gear would be hauled completely and inspected. Perhaps a half hour, if we were lucky, of mending would enable it to be shot again. But it might take longer to replace a whole panel (but quicker than trying to mend it at sea!), so a quick rummage among the stores would find a spare panel, and the old one cut away. Occasionally we had to struggle or even change our direction of pull. Occasionally it just came up very heavy; not, as one would expect with a large boulder (pretty rare) but more likely a piece of junk. Part of a wreck, usually metal, or an old mine case or some other armament. Sometimes it would be too heavy to lift aboard and extricate, and would have to be cut away (incurring more mending aboard) over the stern. But in such situations, with gear hanging in the water while we worked there was the added risk of tail-piping (getting something round the propeller). We were taking a risk, though, by shooting away again without completely hauling; we could be towing for another couple of hours with a great rent in the belly!

One is never satisfied! However well we were fishing, and certainly if we were disappointed in a haul, we were always anxious to try new ground. So we tried at least one tow over new ground each trip in the hope of finding a nugget. So we pushed the bounds of our known grounds all the while.

But sometimes the weather called the tune, usually to send us home, or on occasions to the nearest harbour. For us Mevagissey was the usual; we could tie up there at all states of the tide. But we sometimes sheltered in Fowey, where we moored alongside one of the harbour tugs for a temporary respite. But occasionally, in a strong northerly we would run inshore to the lee of the land, and try our luck. (It was on one of these forays into the unknown, running before a very stiff north-easterly, that we had our biggest haul of Lemons in a single tow. I don’t remember what it was, at this distance in time, but I have the feeling it was 42 stone (266kgs.) But we’d pulled the wing-ends aboard and were heading for home, beating into a very dirty sea towards a lee before one of the crew came in and told me what we’d turned away from! And even though we went back to the same ground the next time we were out, we never repeated it. I think, with the strength of the wind, and all astern of us, we covered a lot of ground in three hours.)

“STOCKER”.

Obviously the catch was put ‘through the books’, and it was in the interest of both the Company and the crew to gather what they could that was saleable. But another of the anomalies of share-fishing was that some of what was caught didn't go ‘through the books’, and it was not obligatory for the crew to save it. But if the crew did take the trouble to save it, and land it, they could share the proceeds among themselves, tax-free. So curiously, even when “scalloping”, other shell-fish was treated as stocker. So lobsters, crayfish, queens (queen-scallops), cuttle, squid, ‘ollies” (octopus) and especially “spiders” (spider-crabs) were all kept as stocker. When scalloping in our later years on the Vigilance, we used to rig a heavy-duty tarpaulin between the bulwarks and the engine-house casing on the port side, and keep this full of water from the deck hose to keep all the spiders in. (A home-made viviere. In the fishing sense, this is any structure that will keep a catch alive. So we have viviere-holds in fishing boats that are water-tight holds as far as the vessel is concerned, but has holes in the hull to allow the free flow of seawater to and from the hold. Typically in crabbers. Or viviere lorries/trailers which can carry live catch in oxygenated tanks.) We could save as much as a tonne or more from a week's scalloping off the Wolf. But we would have to arrange for our Agent to order a vivere lorry (usually Spanish) standing by for our arrival on Saturday morning. But this might very well be the same company as the buyer of our scallop catch, which of course would be in bags. Very nice money! But scallop dredges also caught quite a lot of Turbot and Brill! (We did well out of fish for home when scalloping, because the dredges damaged quite a lot of fish, so that it was unsaleable, even as stocker. We would not otherwise have been eating Turbot or Lobster!)

When we were “white fishing”, the scallops also became stocker.

But apart from livestock any saleable scrap metal was also collected. Especially close in to Rame Head, where the admiralty used to dump a load of rubbish (from dredging), we also collected a lot of aluminium waste.

BY-CATCH.

Among the “by-catch”, we occasionally hauled up bits of “armaments” in various stages of decay; of value to the crew for stocker were the numerous brass shell cases, obviously jettisoned overboard during firing practise by the Navy in the Channel.

Not stocker, but none-the-less valuable, was the coal. When trawling we occasionally picked up quite large (10-30kg) lumps of coal. Enough to make it worthwhile collecting. Not natural deposits, but probably steam coal from sunken ships or even colliers. Being very much lighter than most natural stones it will probably roll around on the surface of the seabed for years. With time that source will dwindle. I wonder if it is still found?

Among all the “hitches” marked on our fishing charts (in red) where quite a lot marked as “mine”. Unlike rocky hitches, these could cause a lot of serious damage to the trawl. They are rusting away, and usually pretty fast (tightly embedded in the bottom), so they tend to tear the net when caught. (A rock tends to just catch the foot-rope and this can be lifted off without doing any damage.) But occasionally we would “catch” a mine. Rather than just tearing the net free, the mine would get entangled in the gear and we would lift it in the trawl. If we were lucky it would be a mangled mess of rusty iron which we hauled aboard to disentangle. And repair the damage to the net. If we were unlucky, and it only happened to me once on the Karen Marie, it would be too heavy to haul aboard. If we could haul it short we could probably see what it was. If not we would have to cut it away. And suffer the repairs to the gear. If we knew it was a mine, or suspected it, we would lower it away and tow it back to just outside the Breakwater, and then pay away from it and call the Longhouse (the Admiralty Port Authority) and ask for the Mine and Bomb Disposal Unit. On the one occasion it happened to me on the Karen Marie I couldn’t tow it, so I waited all day for Doug in the Stella Marie to tow me in to the breakwater later that evening. He left me just outside the Knapp buoy, and I had a sleepless night waiting for the MBDU to come next morning. They laid a charge on it and exploded it remotely. It didn't make much of a bang, so I suppose there wasn’t much explosive, if any, left in it. Anyway, I got my mangled trawl back.

On one occasion I was steaming towards home in the Vigilance, empty, after a night searching for mackerel, and I was crossing the bay off Falmouth. All was peaceful when the boat suddenly shook and I heard a rattle. I shut down (knocked out of gear) and looked over the port side where the noise had come from. Several of the crew appeared from the galley, so they had obviously heard something too. My first thought was that a back-chain had fallen back over the side and touched the prop, but all appeared to be in order. But then I heard someone calling me on the radio. (“Vigilance! Vigilance! Vigilance! Snowdrop! Are you getting me Tony?” Not sure now whether it was the Snowdrop. I think the Snowdrop was a Mevagissey boat.)) About a mile off our port quarter we’d passed the Snowdrop hauling. It appeared that she’d almost hauled the gear home when there was an explosion. Obviously she’d caught a mine. But it shook up the hull and plumbing in the engine room, although his engine was still running. And he asked me to stand by him and escort him into Falmouth. Which we did.

On the Karen we’d hauled up several segments of stone that looked like a green sandstone. They were like slices of an orange segment, from a circle of about 2 ft. diameter, with a “hole” in the centre of about 6 inches diameter. Each segment was about 4 inches thick. Stones like this would normally be thrown back over the side, when we got off towing grounds on the way home. But for some reason we brought three or four home with us. We kept one on the deck of the Karen and were using it as a sharpening stone for our gutting knives. A couple ended up in the workshop and were used to raise metal-work off the concrete floor for cutting or welding. I brought two or three home to make some ornamental steps in the garden. But it appears that someone had spotted some in the mud, flung overboard where we often careened vessels against the North Quay of Sutton Harbour for “painting up”. Whoever, they recognised them for what they were. So the upshot was, that on a quiet Saturday afternoon (the football cup final was on the TV), when not a soul was to be seen, normally, up and down our lane, a great big glaringly painted Mine and Bomb Disposal Unit Land Rover stopped outside my gate, and someone was hammering on my door. That made all the heads pop out down the lane! It wasn’t sandstone; it was Hexanite, a castable German explosive. So they were coming round collecting it all up, and Mary lost her steps.

|

| A hexanite block. |

Of more interest probably was a beautiful decorated porcelain pot, rather like a teapot in shape, but no spout, but a handle on each side. Obviously once had a lid. It looked valuable to me, and miraculously appeared to be undamaged after its rude disturbance by a trawl. I asked one of the crew to put it safely in the wheelhouse, and he put it down awkwardly and broke one of the handles!

We took it to the Plymouth museum and it was identified as genuine sixteenth century Chinese. Another artefact was a part of a clay amphora, about 4 inches tall, part of the rim. This was also identified by the Museum as genuinely old. I seem to remember Phoenician! (In the household of a one-time potter they have got lost now among all the other pottery we have. But I’m sure it is still here somewhere.)

QUEENS.

But another variation on bottom trawling was Queen Scallops. These are the smaller cousins of Scallops; convex on both shells, but only a couple of inches (5cms) across. They seem to scare readily by approaching trawling gear, and we often found them meshed up in the top of the mouth of the box trawls, so they must have swum up to a couple of fathoms (2+ m.) off the bottom. They were a considerable nuisance in so far as they were a major constituent of the “rubbish” we would have to shovel back over the side every haul. Doug often remarked that the only way to get rid of them was to find a market for them. So Mick and I decided to pick up a few baskets-full of larger ones and try landing them for stocker. In fact they sold quite well, so we started landing more and more, until we decided it might be worth while fishing for them. Which we did for a spell.

But to go back a stage, there was a time when we were fishing for Lemons off the back of Hatt Rocks when we started getting so many Queens in the gear at night that it was chafing out the gear, and clogging up the cod end. So after the dimpsey (sunset) haul (and this was during the winter months, so that would have been any time after about 8pm.) we would pull the ends aboard and steam into Mevagissey. (It developed into a race to get in before the pubs closed. The first man ashore would drop our lines over a bollard and hare off up the quay to get a round in before ‘time’ was called, while the rest of us finished off berthing and shutting down. But we would be away again before about 6 am to get the dawning haul in.)

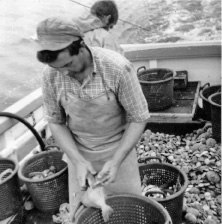

|

| Most of the "rubbish" on some ground was Queen scallops. Look at what is left behind in this haul after the fish has been picked out. |

Anyway,

the Queen fishery developed to such an extent that several of our

boats, and some of the other Plymouth boats, found it worth-while to

convert. We were still using the box trawls, but we were able to stay

on safer ground to the east of the ‘Stone where we caught cleaner

Queens only. We even had DAM Engineers (of which more later) making scallop washer/sorters

for installation on deck to make the job of sorting out the smaller

shells easier. The catch was bagged and landed every day

Next: Compny Progress, Navigaton, Spratting.

Comments

Post a Comment